When still only 18, he was already expressing "nostalgia for the past" five years later, he described himself as "haunted by the fear of seeing youth end". Fournier was a rare exception to this psychosocial rule. In adolescence we all normally dream of "coming to man's estate". This contains the undermeaning of "estate" in the sense of "passage of life". Or The Lost Domain, which held sway until the recent Penguin edition (translated by the late Robin Buss) improved it into The Lost Estate. A sideways approach works better, as with The Wanderer, which identifies the hero's restless nature.

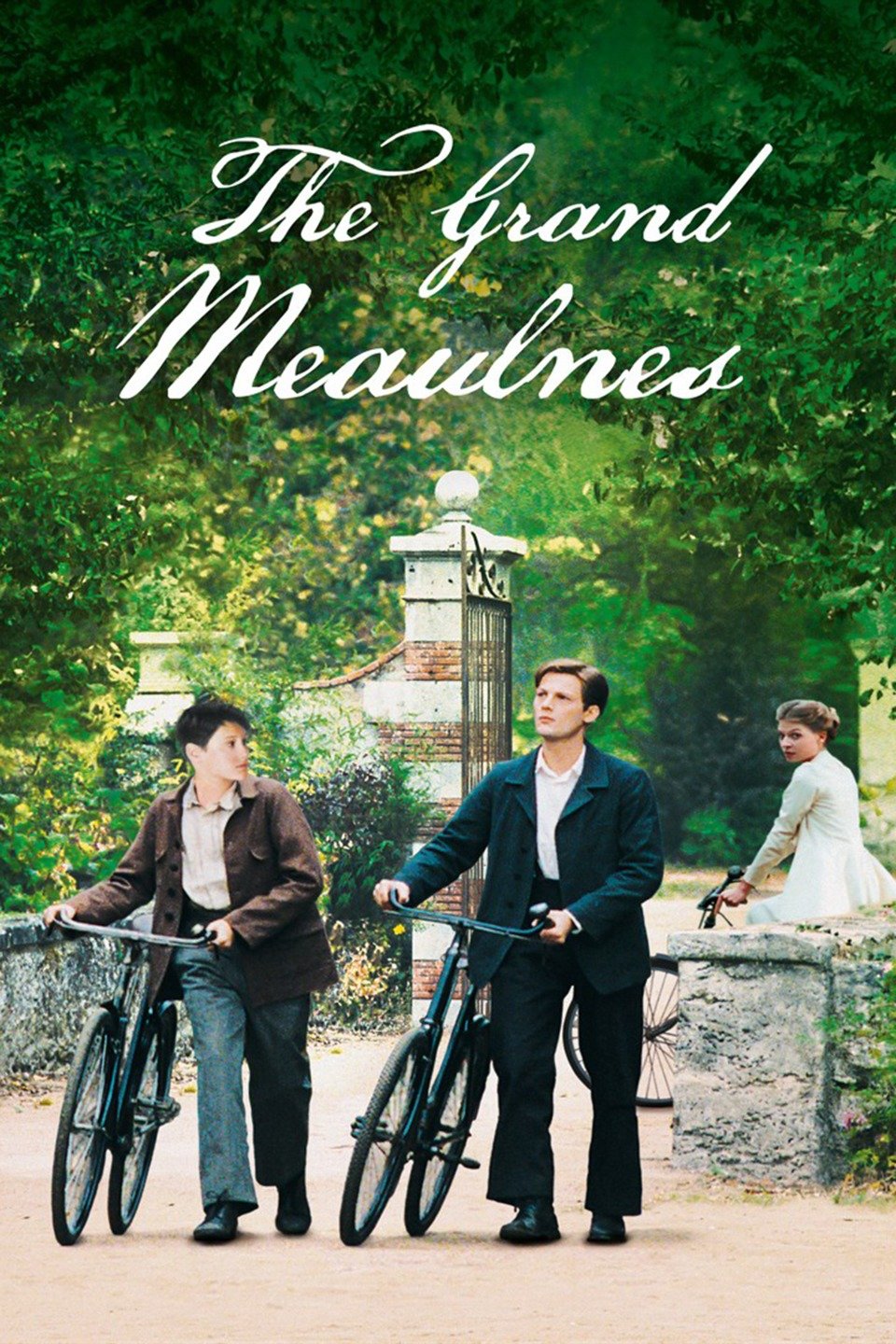

Some translators simply leave it in French. Meaulnes is the surname of the chief character, but in English an unfortunate homonym of "moan" so to call the novel The Big Meaulnes or The Great Meaulnes or (even, recently) The Magnificent Meaulnes is asking for trouble. The title is, admittedly, a problem it's been said that there are more English titles for the book than there have been translations. More likely, I was still too young for it. I imagined a sentimental tale of rural life, and wrongly assumed I was too old for all that stuff. For a long time I'd been put off by the title (as I had with The Catcher in the Rye), by a paperback cover featuring a cute chunk of French chateau peeping out from idyllic woodland, and by the blurb, which would announce the story of a boy finding a mysteriously beautiful house then losing it, and finding a mysteriously beautiful girl then losing her. I first read it even later than most – towards the end of my 30s. The British generally come to the book later than the French. What John Fowles called "the greatest novel of adolescence in European literature" can only ever be partly grasped by adolescents, because they don't yet know exactly what it is they are going to lose by growing up. This may stem from an understandable reluctance to revisit set texts but more, perhaps, from a fear that the novel's magic might not work a second time around – as if, in adulthood, we know too much to fall under the its spell again.

Most French people read it at school yet very few of them (according to my own private poll) ever reread it. A poll of French readers a dozen years ago placed it sixth of all 20th-century books, just behind Proust and Camus. There is no doubting the classic status of Alain-Fournier's Le Grand Meaulnes.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)